|

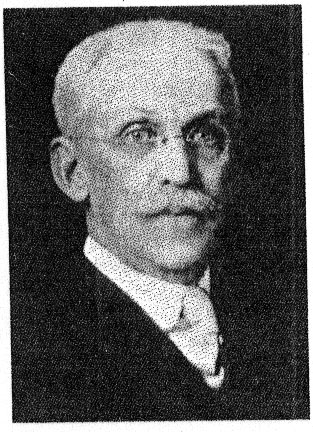

Volume 21, pages 173-177, 1936 MEMORIAL OF EDWARD SALISBURY DANA WILLIAM F.FORD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Edward Salisbury Dana, the Dean ofAmerican mineralogists, died on June sixteenth, 1935, at his home in New Haven.In order to appreciate properly his position and influence one must considerbriefly the history of his family. The following dates are significant ones, notonly in the family records, but in the annals of American science. BENJAMIN SILLIMAN Born August 8, 1779. JAMES DWIGHT DANA Born February 12, 1813. EDWARD SALISBURY DANA Born November 16, 1849. The above is without doubt a unique family record. For more than one hundredyears these three men, grandfather, son and grandson, were leaders in Americanscience, not only by their own contributions, but even more through their booksand the journal which they established and maintained. It is not necessary toenlarge upon these facts; the bare record is sufficiently eloquent. It was natural that Edward Dana should on graduation from Yale turn hisattention to science and in particular to mineralogy. He studied for two yearsunder Professor George J. Brush of the Sheffield Scientific School and then wentabroad where he worked for two years at Heidelberg and Vienna. At the latterplace he studied with Tschermak, Lang and Schrauf. His stay there must have amost fruitful and pleasant one. He learned the methods of investigation incrystallography and crystal optics, fields in which most of his originalinvestigations were to lie. He also made many friendships which were to endurethrough the years and which led him to help in the relief of the impoverishedVienna scientists in the dark years after the war. Many members of theMineralogical Society of America answered Dana's appeals and know personally howhe conducted this friendly work. It seems appropriate to record here in part thegreeting sent to Dana by the Vienna Academy on his eightieth birthday. "We recognize you as the master and leader of American mineralogists and weof Vienna may rightfully claim Edward S. Dana as one of ourselves. Since 1873bonds of personal friendship have been formed between you and a number ofphysicists and mineralogists in Vienna.... With this circle of friends you havekept faith during one of the saddest times which Vienna and Austria have everexperienced.... We all think of you with lasting gratitude." After his stay abroad Dana came back to New Haven and his work at Yale. He tookthere the M.A. degree in 1874 and the Ph.D. degree in 1876. While his teachingat Yale was largely in physics, at which he was most successful, his scientificinvestigations and writings were almost entirely concerned with mineralogy. Hisbibliography is a long one and cannot be given here but will be publishedshortly in the Transactions of the Geological Society of America. A fewcomments, however, should be made upon it. Hepublished in 1872 the first paper in America to deal with the investigation of arock from the petrographic point of view. His doctor's thesis was on "The Trap Rocks of the ConnecticutValley" and was the first important petrographic memoir to be publishedhere. The record shows that he published the results of investigations on atotal of at least fifty-five different mineral species. In the sixth edition ofthe System of Mineralogy the crystallographic axial ratios of the followingtwenty species are credited to him; beryllonite, chondrodite, columbite,danburite, dickinsonite, eosphorite, fairfieldite, fillowite, herderite,hureaulite, monazite, pectolite, polianite, reddingite, samarskite, stibnite,triploidite, tyrolite, tysonite and willemite. He was in part responsible forthe description of ten new species, namely dickinsonite, durdenite, eosphorite,eucryptite, fairfieldite, fillowite, lithiophilite, natrophilite, reddingite andtriploidite. From the above one can see that Dana's research was varied and of noinconsiderable amount. It was, however, through his books that he made hisgreatest contribution to mineralogical science. His first volume, which waspublished in 1877, was the Textbook of Mineralogy. A book of this type had beenplanned by his father but ill health intervened and he turned it over to Edwardwho was only twenty-eight when the book was published. (James Dwight Dana hadpublished the first edition of "The System" when he was twenty-four!)The Textbook is still in active use, the second edition being published in 1898,the third in 1921, and the fourth in 1932. All mineralogists will agree that Dana's greatest contribution to mineralogy andthe one upon which his fame securely rests was the publication in 1892 of thesixth edition of the System of Mineralogy. The fifth edition had been publishedin 1868. There was, therefore, an interval of twenty-four years between the twoeditions. This period was one of active mineralogical research and a greatamount of new data had accumulated during it. The sixth edition was therefore ingreat part a new book. Further it was in all essentials the work of one man. Dana enlistedclerical help in the recalculation of the crystal angles and in the redrawing ofthe crystal figures and of course had advice and assistance from a great manymineralogists the world over, but the entire direction and a very large part ofthe actual work was his alone. It probably took him about ten years, but duringthis time he was actively engaged in college teaching and administration, and inhis duties as an editor of the American Journal of Science. It was a very greatburden that he carried in that period and it is not surprising that when it wasover his health was impaired, and during the subsequent years his activities hadto be much curtailed. The sixth edition was remarkable in many ways. Its accuracy has astonished allwho have used it. There were so many chances for errors and misprints and so fewhave ever been found. The judgment shown was so keen and well-balanced thatmineralogists have frequently referred to it as the "mineralogists'bible." A study of the material included in the paragraph headed REF. atthe end of the descriptions of species will show clearly how Dana balancedconflicting ideas and formed his conclusions concerning contradictory data. Inmany instances he published here the results of his own investigations which hadnot been printed elsewhere; two instances being the crystallographic data forpectolite and willemite. Considerable material was also supplied by otherinvestigators in advance of publication elsewhere. Unquestionably this book,even today more than forty years after its publication, remains the mostimportant contribution to mineralogical science that has come from America. The American Journal of Science is the oldest scientific magazine in thecountry. Established by Silliman in 1818, the journal was edited and financiallymaintained by him and the two Danas until 1926, a period of one hundred andeight years. Edward Dana was its directing force for upward of forty years, andin fact continued an active interest in its affairs until his death. As aneditor he made his second most important contribution to American science. Fortunately many American mineralogists at one time or another came intopersonal contact with Dana. They were familiar with his great charm, hisunfailing good humor, his modesty and his delight in being able to offerassistance. He was the most delightful and entertaining companion, full of aquiet humor and ready with an appropriate story or reminiscence. Until veryrecently he was physically vigorous and delighted in long walks and climbs bothabout New Haven and among the hills of Mount Desert Island where he had hissummer home. For years he was accustomed to ride about the streets of New Havenon a bicycle, and only relinquished the habit when his family protested that hisage and the increase in motor traffic made the practice too dangerous. Heprobably owned an overcoat but the present writer cannot recall ever having seenhim wear one. His only concession to winter weather was the occasional wearingof a light sweater under the coat of his suit. With his death Yale and New Havenhave lost one of the last of the old-time gentleman scholars who contributed solargely to their fame. Many honors came his way. We cannot do better here than to quote the concludingparagraph of Professor Schuchert's memoir.1 "His election as correspondingmember of the Vienna Reichsanstalt came in 1874, and this same year he waselected to the Sociedad Mexicana de Historia Natural. At the age of thirty-four,he was placed on the roster of honorary members of the ancient MineralogicalSociety of St. Petersburg. Acclaim in his own country came also in that year,with his election to the National Academy of Sciences, the greatest honor thatcan be given to an American scientist. At his death, he was the second oldestmember, the oldest one having been elected in 1883. He was also an honorarymember of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (Boston), the AmericanPhilosophical Society (Philadelphia), the Geological Society of America, and thePhysical Society of America; a foreign member (1894) of the Geological Society,London (corresponding member 1888); and a member of the Edinburgh GeologicalSociety, the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain, the Philosophical Society(Cambridge), and the Vienna Academy. He was honored at the 300th anniversary ofthe University of Dublin. In 1925, the Mineralogical Society of America electedhim Honorary President for life; in 1934 the Mineralogical Club of New York Citymade him an honorary life member, and the American Museum of Natural Historygave him the same distinction. The Yale Corporation, meeting on the day of hisdeath, passed a resolution of which the following are the closing words:'Foremost American mineralogist of his time, he brought to himself and to theUniversity widespread recognition in the world of science'." NOTE 1 Am. Jour. Sci., vol. 30, p. 161, 1935. [var:'startyear'='1936'] [Include:'footer.htm'] |